The Census Projects are a collaboration across different departments including Anthropology, English, History, and Photography.

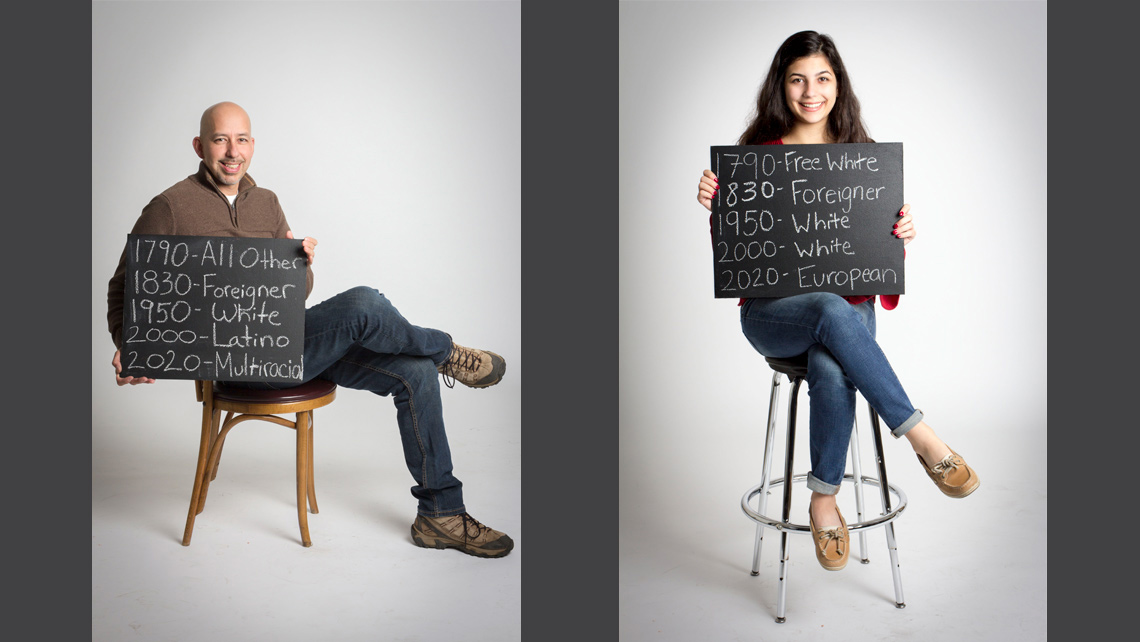

The Census Projects asked students, faculty, and staff at Cosumnes River College to answer the race/ethnicity and sex questions on historic censuses and to choose how they would have been identified by the government at that time. These photos are currently on display in the CRC Library.

Gender and Sexuality Photo Exhibit

Race and the U.S. Census Photo Exhibit

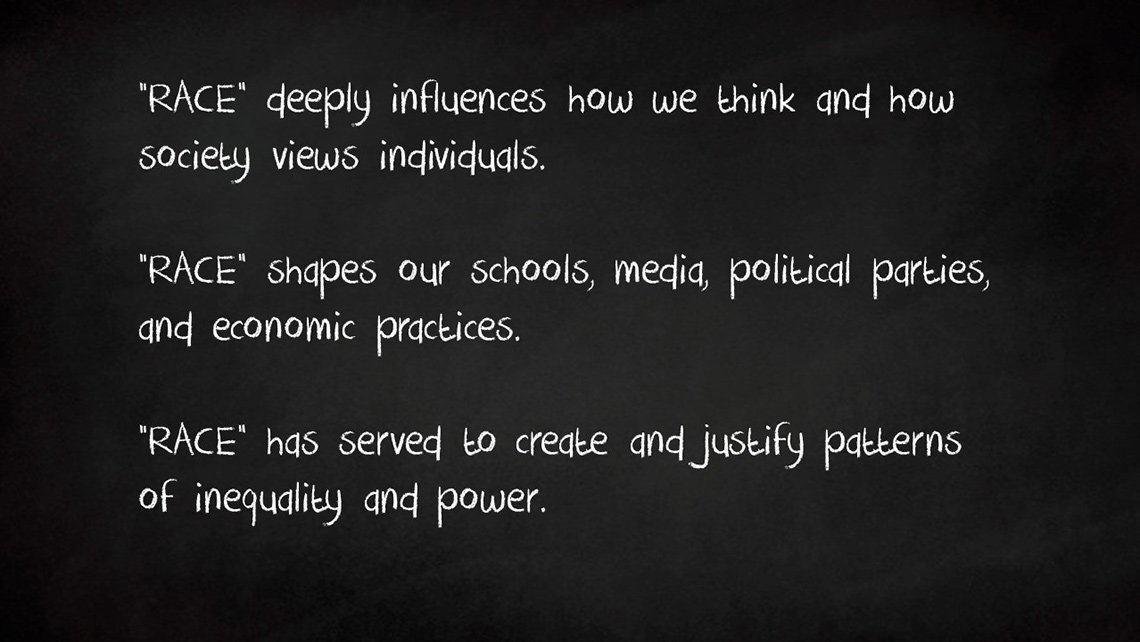

The US Census determines how federal funding is allocated to people living in the United States. While some questions, such as a person's age, may seem straightforward, other questions such as a person's ethnic, racial, or gender identities are not.

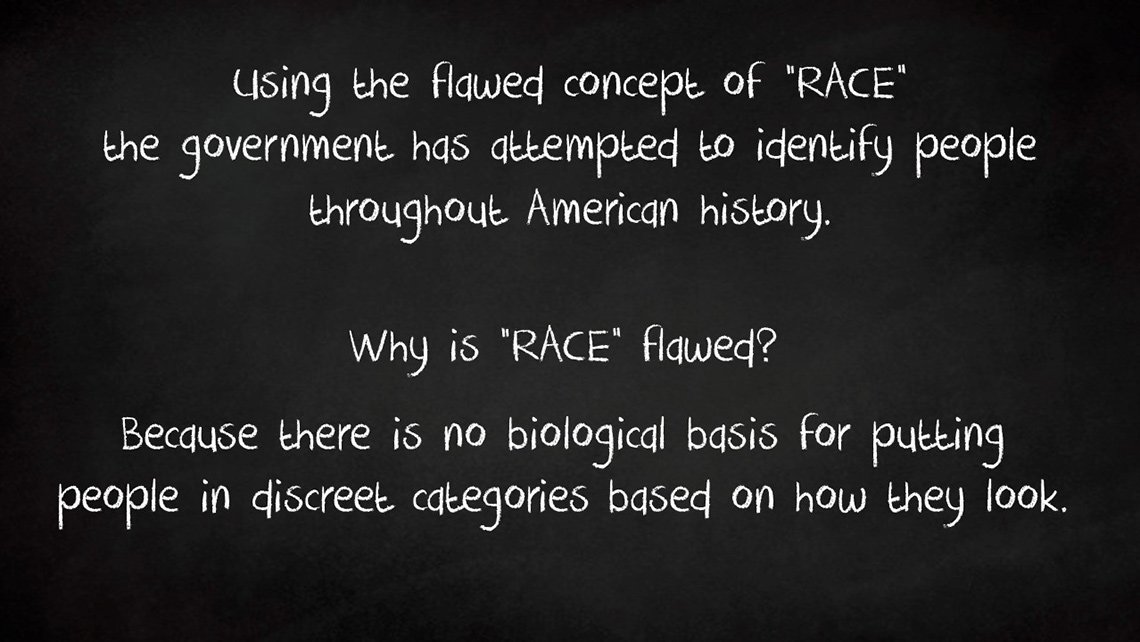

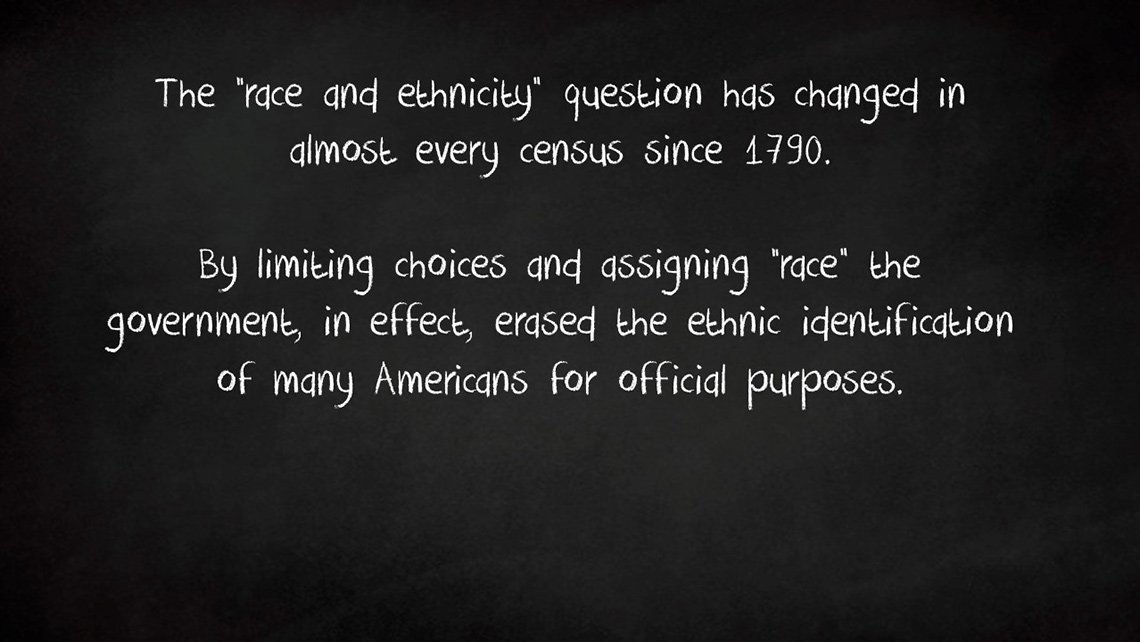

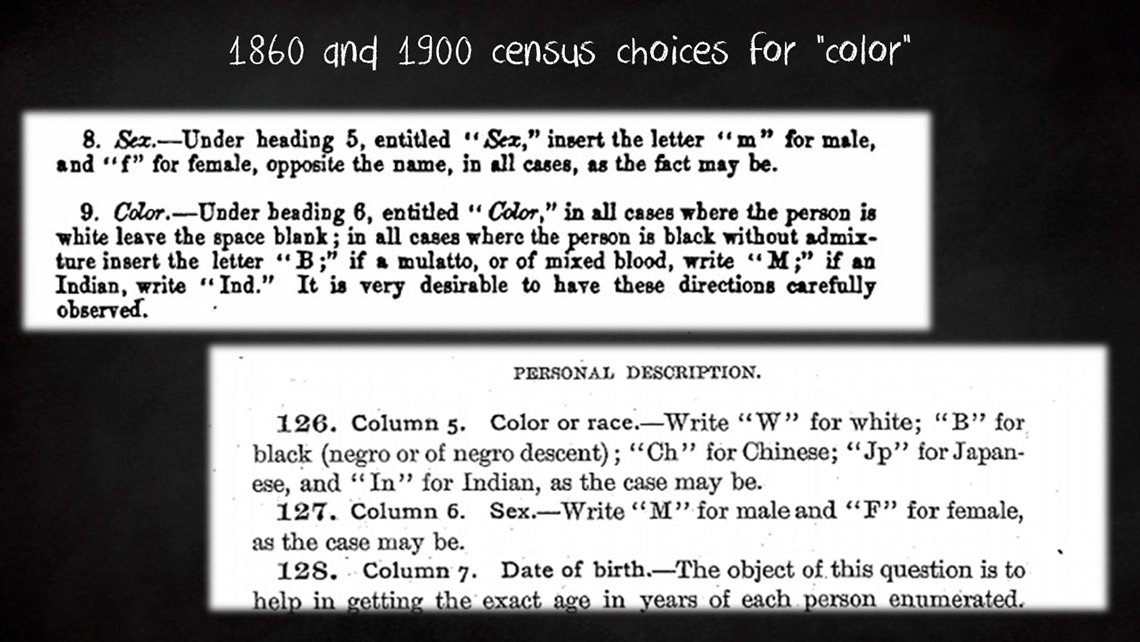

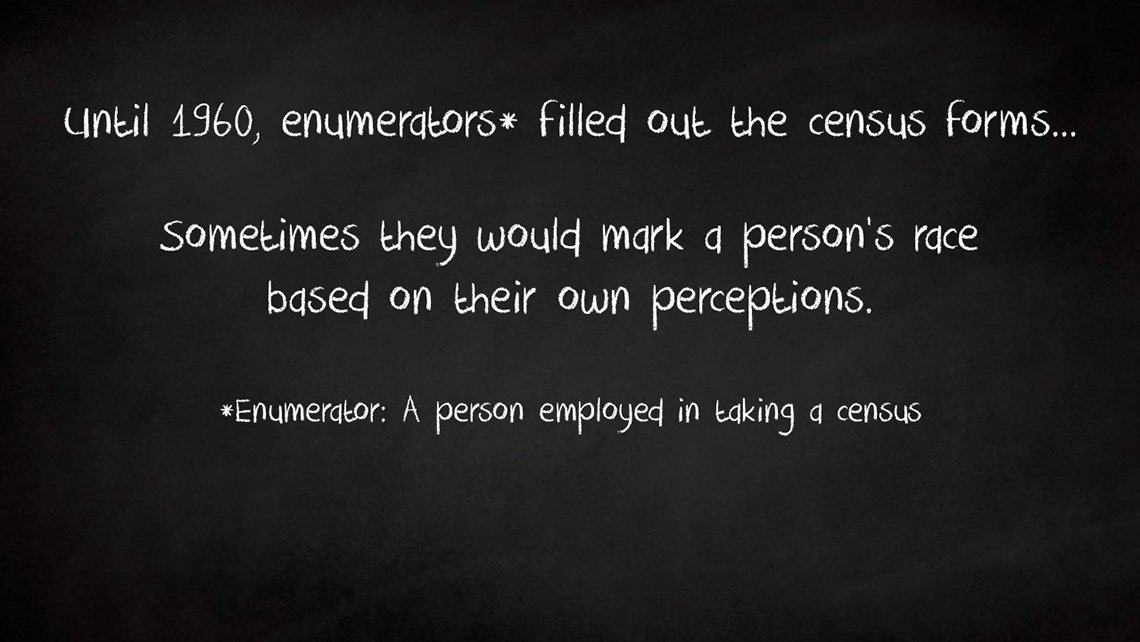

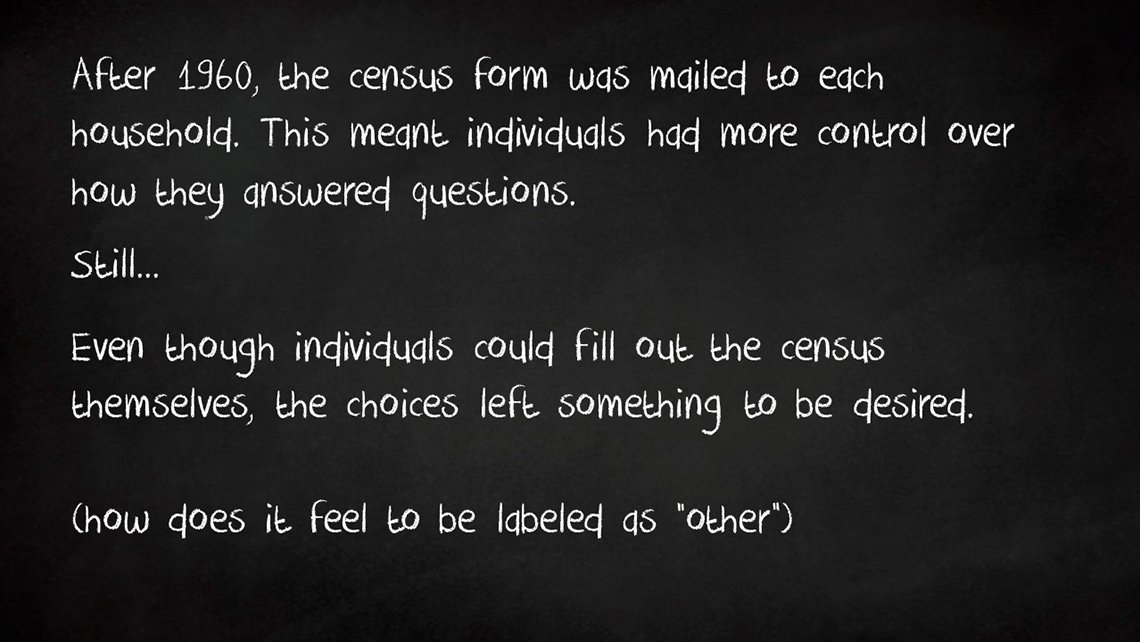

Since the first census in 1790 what constitutes "race" has changed dramatically, illustrating an important point - that race is a social and cultural construction that reflects contemporary relationships and not a biological fact. Conversely, the sex question has never been modified and the listing of sex as a binary (male or female) compels individuals to choose one or the other. Prior to 1960, the enumerators who collected census data would choose a person's sex and racial identities if there was any doubt or if an individual didn’t give an answer.

The Census Projects asked students, faculty, and staff at Cosumnes River College to answer the race/ethnicity and sex questions on historic censuses and to choose how they would have been identified by the government at that time. For example, the same person could be listed as Japanese in 1890, Korean in 1970, and Asian in 1990. Another person would have been counted as a slave in 1820, a mulatto in 1870, and a Negro in 1960. Although it might not seem apparent, it’s important to note that the shifting racial and ethnic constructions created by the Census also operated along gendered lines that secured white heterosexual identity. The earliest formulations of the Census that counted the enslaved Black population as “slaves” for example, viewed Black people as having no gender because they were nonpersons and the “property” of whites. Inevitably we learn that how we conceive of ourselves is quite different than how the government or society at large views us.

The U.S. Census has also never collected information on a person’s gender identity or sexual orientation (even though these identities can be the basis for discrimination, harassment, and bias). It has been assumed and enforced throughout our history that all people are cisgender – meaning their sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation align as either male/masculine or female/feminine and always heterosexual.

The goal of the Census Projects is to educate and provoke discussion that labels not only matter, but that they influence the very government support undercounted communities need. We hope in the future to see census categories that are more expansive, intersectional, and frankly, humane. Everyone counts. Given the choice, how would you like to be counted?

The Census Projects are a collaboration across different departments including Anthropology, English, History, and Photography. Thank you to Kathryn Mayo for creating the portraits, Anastasia Panagakos for conceptualizing the project, José Alfaro for outreach to the LGBTQ community, and Diana Reed for providing historical context. These projects are a variation of an exhibit of the Race Project first created by the American Anthropological Association (AAA). These projects received funding from the Cultural Competency and Equity Committee.

Finally, a special thank you to all in our campus community who posed for these portraits!